I noticed Will Self‘s tired article on the death of the novel a couple of days ago but, having skimmed through it, I felt it really was not worth reading but a tired rehash of the old story, not least the idea that the idea of the novel being dead really meant that people aren’t buying Will Self’s book. And who can blame them? I read Umbrella, only because I had vowed to read all the short list for the Man Booker that year (2012) but I found it a very tiresome and uninteresting novel. The pity was that it had a good idea but Self had messed it up by being resolutely post-modern. You know the sort of thing – disjointed plots, people speaking but you have no idea who is speaking, quotes from pop songs, etc, etc, etc. I have dipped into a couple of his other novels and found them equally tiresome. However, reading the Guardian Review in the bath, as one does, I came across the print version of Self’s article and more or less persevered. (I do tend to read the Guardian Review in the bath, though there is a slight disadvantage, as the Guardian sometimes has this annoying habit of having one page printed on a single sheet instead of a double sheet, and this occasionally falls in the bath, which can be inconvenient. It is not the only annoying thing about The Guardian.)

While we are doing annoying, I have to confess to finding Self annoying. When you see him on TV, which I very much try to avoid, or when you read him in the press – he is sadly ubiquitous in the posh British press – he comes across as arrogant, pompous and very much full of himself. The photo on the right of Self holding his book over the heads of the other candidates at the Man Booker promotional photo shoot is an example. I have to admit, I was expecting to be annoyed by Self’s article and I was not disappointed. Conversational Reading had already expertly trashed him, so I thought I might just focus on his language. In the first sentence he used the word benison. At first I thought it was a Guardian type for venison. For non-UK readers, I should point out that the Guardian is famous for its misprints and, indeed, is often known as The Grauniad to reflect this. I soon realised that it was not a misprint. I vaguely recalled what benison was, not least because it comes from the French bénir, meaning to bless. However, I can safely say that it is a word I have never used and do not recall seeing used outside a religious context. He goes on to talk about queered demographics. As he must know and we all do, queer and queered are now used by the gay community to refer to gays and gay issues. But just as only blacks can say nigger (ask Jeremy Clarkson; on the page on the Self article linked to above, there is a reference to Clarkson begging for forgiveness for using it (this may differ for you, depending when and from where you link to the page)), it is generally not PC for non-homosexuals to use queer. I could go on about his use of language but I won’t as it is very boring for me and very boring for you.

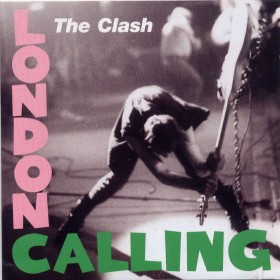

Self’s thesis starts with one of his canaries. Canary seems to be the word he uses for children. This is partially explained by the fact that the canary he is mentioning is an aspiring rock guitarist but, as he uses it to refer to all of his children, it seems that it is not used in the sense that canaries are known songbirds. He bangs on about how music has changed with the advent of the web. I don’t entirely agree with him but we are here to talk about the death of the novel. He starts In the early 1980s, and I would argue throughout the second half of the last century, the literary novel was perceived to be the prince of art forms, the cultural capstone and the apogee of creative endeavour. It was? Classical music? Fine art? Opera? Theatre? And what novels does he cite to bolster his arguments? Those well known 1980s novels Ulysses and To the Lighthouse. What was happening in the early 1980s in the novel? Sticking only to the English novel, the likes of Anthony Burgess, Lawrence Durrell and John Fowles were fading away, Doris Lessing was on her sci-fi thing and the likes of Julian Barnes, Graham Swift, Ian McEwan, Peter Ackroyd, Pat Barker, Kazuo Ishiguro and Martin Amis were getting going. Oh, young Will was reading PPE at Oxford. That’s Politics, Philosophy and Economics, not Literature. To be quite honest, the works of those young writers (and the old writers) were not nearly as important and relevant as a work that appeared two weeks before the start of the 1980s – The Clash‘s London Calling.

Of course, there were some interesting novelists around at this time – Héctor Aguilar Camín, Ismail Kadare, Cees Nooteboom, Carlos Rojas, Michel Tournier, César Aira, António Lobo Antunes, Max Frisch, José Saramago, Hugo Claus and Christa Wolf – I am guessing he was not referring to these. They have a couple of things in common. They were written in languages other than English and they were not written by Will Self.

He goes on. Those who reject the high arts feel not merely entitled to their opinion, but wholly justified in it. (For which read, those who reject Will Self novels feel wholly justified in it. Yes, Will, I do.) Of course, the readers of Barbara Cartland, Jeffrey Archer and other low-brow writers have always felt justified in damning Ulysses and To the Lighthouse and, frankly, I do not blame them. Neither is an easy read and both require a certain amount of commitment, learning and dedication to fully appreciate and, if people do not feel like giving this commitment, learning and dedication, I, for one, do not mind. However, Self’s arguments come down to five things. 1) E-books are bad (but I use them). 2) Amazon is bad (but I use it). 3) The gatekeepers who kept us away from the crap are disappearing and now crap is everywhere. 4) Creative writing programmes are bad (even though I teach one). 5) My first book was not published in hardback. What an affront! 1, 2 and 4 have been regurgitated on websites and in blogs galore. I do need to add anything except to say I have generally found both 1 & 2 positive from my point of view, though I can understand why authors are less enthusiastic. As for 3, did the gatekeepers really do a good job?

Self likes slinging in a few quotes so here is one. The great American novel has not only already been written, it has already been rejected (Somerset Maugham). In short, the gatekeepers rejected many great novels and promoted many crap novels. A free-for-all democracy, where anyone can publish a novel on the web, with self-publishing or in Kindle format and sell it through Amazon is, I think, a good thing. The gatekeepers are still there. The literary reviews in newspapers or in the better quality reviews like the TLS or NYRB still review (primarily) books that have been published in hard copy and by accredited publishers. That does not mean that Will Self is going to be reviewed before E L James but it does mean that someone somewhere is making a judgement, however flawed, as has always been the case. And, yes, there are many blogs and websites that do review on-line books and good for them. The likes of Smashwords are to be encouraged.

The current resistance of a lot of the literate public to difficulty in the form is only a subconscious response to having a moribund message pushed at them, he states. In other words, all too many people do not like Self’s deliberate obfuscation (a nice Selfian word) either in this article or in his novels. I have read many difficult books. Yes, Will, I have read Finnegans Wake and enjoyed it. I enjoyed The Pale King, which many did not. I love William Gaddis. But all of these writers had a point to their difficulty. If there was a point to the difficulty of Umbrella, I missed it. I had the feeling from reading the book and reading Self’s comments on it that the difficult style was the point. He could have made it more readable without losing anything but chose not to.

In conclusion, I will say one thing (though I could say a lot more). In 1960, if you wanted to be considered well-read in the contemporary novel, you would have had to read a fair amount of novels from the UK, US, Ireland, France and perhaps one or two other countries. You might have read the odd novel from Italy, Germany, Japan, Scandinavia and China. Indeed, unless you could read other languages, you probably could not read all that many novels from the twentieth century from non-English-speaking countries. I have reviewed books from 209 countries on my website. While you do not have to have read books from all 209 to be considered well-read in the contemporary novel, you certainly should have read books from at least twenty-five different countries and probably more. The novel dead? Of course it isn’t. People are reading. More and more books are being published every year and that is excluding the many, many ebooks that are not published in hard copy and it also excludes self-published books. While many of them may be non-fiction, reprints or plain crap, I find that every year there are more and more books I want to read because more and more worthwhile book are being published, both in the English-speaking world and elsewhere. Have you been to Latin America recently, Will? They are reading books there – good books – and writing them and talking about them. The novel dead? Hell, no. Maybe it is just you who are.