A second covid year, and undoubtedly not the last has meant, for me, much less travel and none abroad and much less going out – I cannot remember the last time I went to the cinema, theatre or a pub and while I can remember the last time I went to a football match, it was well before lockdown. This has meant more time for reading as well as more time for walking and doing stuff around the house but also more of the covid lethargy which seems to affect people.

As in most years, there were some books I read that I had not heard of by December last year and even some authors I had not heard of. Indeed, there were even a few publishers I had not heard of. The publishers I read most from were Columbia University Press (five), Dedalus (five), New Directions (five), Deep Vellum (five), Archipelago (four), Fitzcarraldo (four), Istros (four), Two Lines Press (four), Europa (three) Fum d’Estampa (three), Hoopoe (three), Open Letter (three) and World Editions (three).

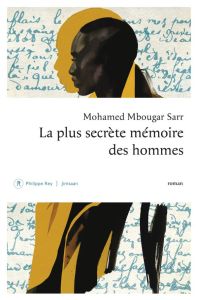

New (to me) publishers were Angry Robot, Bordighera, Dzanc, Éditions Philippe Rey/Jimsaan, Mig-21, Nouveau Monde and Pariah Press.

In terms or nationalities, the main ones were Romanian (twenty-one) Catalan (six), German (six), Japanese (six), Norwegian (six), English (five), Spanish (five), French (five), Italian (four) and US (four). Romania was the country selected for my annual reading marathon.

Less well-represented nationalities included Albania, Belarus, Bosnia, Central African Republic, Chicano, Republic of Congo, Denmark, Georgia, Guadeloupe, Iran, Latvia, Libya, Lithuania, Namibia, Palestine, Saudi Arabia, Senegal, Slovakia, Slovenia, Syria, Taiwan, Tanzania, Uruguay, Uzbekistan and Wales.

In terms of the language the books were originally written in, the order was Romanian (nineteen), English (fifteen), French (fifteen), Spanish (twelve), Arabic (eleven), German (seven), Russian (seven), Catalan (six), Japanese (six), and Norwegian (six). Less commonly represented languages included Albanian, Bosnian, Croatian, Danish, Farsi, Latvian, Slovak, Slovenian, Ukrainain, Uzbek and Welsh.

I read forty-six books by women, almost a third of the total, much higher than in recent years.

I read a total of 141 books with 40983 pages, for an average of 291 pages per book. The longest book was Miljenko Jergović‘s mammoth Rod (Kin) (translated by Russell Scott Valentino, published by Archipelago), about his (very) extended family, weighing in at 800 pages, closely followed by El corazón helado (The Frozen Heart) (translated by Frank Wynne), by Almudena Grandes, who sadly passed away this year. The book is about the scars left by the Spanish civil war and also about adultery. Michel Houellebecq‘s new novel Anéantir [Annihilate], the last book I read this year, came next. Interestingly the fourth and sixth longest books I read were also by Spanish authors – Javier Marías‘ Tomás Nevinson, not yet translated into English, and Agustín Fernández Mallo‘s Agustín Fernández Mallo, published last year by Fitzcarraldo, translated by Thomas Bunstead. The fifth longest was the last book I read this year: Juan Andrés Ferreira‘s Mil de fiebre [A Temperature of a Thousand Degrees].

Early in the year, my annual country marathon focussed on Romania and my conclusion was that I was glad I did not live in twentieth century Romania, for which I was mildly and rightly berated. This was not a criticism of the Romanian people but partially of their various governments and partially because of the unfortunate circumstances they were exposed to, including both German and Russian occupation and being involved in both world wars. I certainly read some interesting books which, I think, were not generally well-known in the English-speaking world and I hope that I showed that Romanian literature has a lot to offer and that there are quite a few available in English.

One other interesting literary thing I would mention is that African writers won four of the major literary prizes this year and I read them all. Abdulrazak Gurnah won the Nobel Prize for literature. I had already read and reviewed three of this books but I added his most recent book- Afterlives. David Diop won the International Booker Prize for his Frère d’âme (At Night All Blood Is Black), translated by Anna Moschovakis, published by Pushkin, about Senegalese soldiers in World War I. Damon Galgut won the Booker Prize for his The Promise about a dysfunctional and racist South African family.

In my view, the best of the four was the only one that is not yet available in English but surely will be – Mohamed Mbougar Sarr‘s La Plus Secrète Mémoire des hommes [The Most Secret Memory of Men] about the hunt for an African writer who had success in France and then disappeared after being accused of plagiarism, based on the story of Malian writer Yambo Ouologuem.

I do not do a best of list, not least because I know that there are a lot of fine books that came out this year that I did not have a chance to read and also my view today may not be the same as my view tomorrow. However, here are some of the books I particularly enjoyed. However, I would add that I enjoyed virtually every book I read this year and, unlike, last year, did not abandon any book before finishing it.

In no particular order… Vladimir Sharov is a superb writer. Sadly he died in 2018. Dedalus have published three of his novels in English and all three are well worth reading. This year saw Будьте как дети (Be As Children) (translated by Oliver Ready), another superb book about children and innocence or sin and innocence, but don’t let that put you off, as it is about lots of other things, particularly Russian history from way back up to Lenin. If I were to pick my favourite book of the year, it would probably be this but, as mentioned, I shall not be picking a favourite book.

One other Russian work I must mention is from Andrei Bely, author of the brilliant novel Петербург (Petersburg). He wrote some fascinating early works which he called Симфонии (Symphonies). I call them prose poems but, whatever you call them, they make for very interesting reading, from the excellent Columbia University Press and translated by Jonathan Stone.

I have read more books originally written in Arabic than I normally do and would single out a couple. Omaima Al-Khamis‘ رواية مسرى الغرانيق في مدن العقيق (The Book Smuggler)(translated by Sarah Enany) was published by the excellent Hoopoe and did not get as much traction as it should. It is set in the eleventh century, when the Islamic world was far more advanced, e.g. in paper making and book publishing than the Western world and follows Mazid al-Hanafi, around the Islamic world. We get a lot of colourful stories, interesting historical and literary tidbits and a lot about Islamic differences. Moreover, this is a book by a Saudi woman, of which there are not many in English.

Another interesting woman writer from the Arabic-speaking world is the Palestinian Sahar Khalifeh, Several of her works have been published in English. I read her الأول : رواية (My First and Only Love) (translated by Aida Bamia) about a woman artist who returns to Palestine after many years abroad. It is , of course, about her lost love but also about the brutalities of the Israeli occupation and told very well.

While we are in that part of the world… The Iranian writer Iraj Pezeshkzad has had two novels translated into English. I read حافظ ناشنيده پند (Hafez in Love) (translated by Pouneh Shabani-Jadidi and Patricia J. Higgins)about the very real Persian poet Hafez, from Syracuse University Press, who publish some interesting books. Yes, it is about love, politics, Islam and, of course poetry and a very enjoyable read.

If you follow me, you will know I like to read a fair amount of Spanish. I will mention a few here. I have not read much from Uruguay but managed thee this year. I have discovered Uruguayan weird fiction and started with Ramiro Sanchiz‘s Trashpunk which, despite the title, has not been translated into English and followed it with Juan Andrés Ferreira‘s Mil de fiebre [A Temperature of a Thousand Degrees].

What has finally been translated is Mario Levrero‘s La novela luminosa (The Luminous Novel) (translated by Annie McDermott), a very long book from the excellent And Other Stories about, well, virtually nothing. Our hero is trying to write this book, The Luminous Novel and, somehow, cannot get round to doing so. We get all his excuses and how he gets sidetracked but, after 544 pages, he still has not written it. A superb novel.

There are two countries in Latin America at the forefront of producing quality writing. The first is Argentina. One of the best and most intelligent writers from that country is Pola Oloixarac. I read her novel Mona (Mona) (translated by Adam Morris). It is about literary conferences, writers, violence against women, political correctness and the French. It is another superb novel from her.

The other Latin American country whose writing really impresses me is Mexico. Mario Bellatin writes short novels but they are first-class. I read two of his this year. The first was one of the two pandemic novels I read this year (though the pandemic in this one is more AIDS-ike than covid-like) – Salón de belleza (Beauty Salon) (translated by David Shook). However, it is not a straight pandemic novel.

The second was Poeta ciego [Blind Poet], which has not been translated into English about a blind poet and a strange sect.

Moving to Spain I really enjoyed Agustín Fernández Mallo‘s Trilogía de la guerra (The Things We’ve Seen) (translated by Thomas Bunstead). The book, as you can see from the Spanish title, was a trilogy. The first book was about a literary conference attended by a writer on the Island of San Simón, an island that has a history, particularly as a prison camp during the Spanish Civil War. The second book is about Kurt Montana who was the fourth astronaut on the first moon landing. The third book is about the writer’s girlfriend’s Sebaldian exploration of Normandy. A brief summary cannot do justice to this complex, superb work.

While we are in Spain, I continue to read works translated from the Catalan. Fum d’Estampa continue to publish excellent works from the Catalan. I enjoyed all of theirs but particularly Raül Garrigasait‘s Els estranys (The Others) (translated by Tiago Miller) about a translator and the subject of the book he is translating, the bumbling Rudolf von Wielemann, a German fighting in the Carlist wars in Catalonia. It is both funny but interesting.

Other publishers do publish Catalan literature and I would mention two. Max Besora‘s Aventures i desventures de l’insòlit i admirable Joan Orpí, conquistador i fundador de la Nova Catalunya (Adventures and Misadventures of the Extraordinary and Admirable Joan Orpí) (translated by Mara Faye Lethem), from the always excellent Open Letter, a tongue-in-cheek account of a Catalan explorer in what is now Venezuela.

Eva Baltasar‘s Permagel (Permafrost) (translated by Julia Sanches) is more serious – a confession, an outpouring, an apologia.

Willem Frederik Hermans is one of the foremost Dutch writers and I read his very readable Herinneringen van een engelbewaarder (A Guardian Angel Recalls) (translated by David Colmer). It is both a serious book about the Nazi invasion of the Netherlands and somewhat critical of the Dutch government but also, as the title implies,somewhat tongue-in-cheek.

I have always enjoyed Susan Daitch‘s works and her Siege of Comedians did not disappoint. As always it was a complex novel, this one about face modelling, Nazis, terrorism, human trafficking, German cinema and much more.

I am always surprised at the most-read entries on my website. No 1 was Ifeoma Okoye‘s Behind the Clouds, a Nigerian novel I read and reviewed some time ago. For some reason Dogra Magra pops up every year. I read Hervé Le Tellier‘s L’Anomalie (The Anomaly) last year but as it only came out in English this year, I can see why it got more traction this year. Wilton Sankawulo‘s The Rain and the Night is another oldie but regular. Other golden oldies doing well are John Barth‘s Floating Opera and Paul Auster‘s City of Glass. The first book I read this year in the list is at No 37: Javier Marías‘ Tomás Nevinson.

A final interesting point. Jonathan Franzen‘s Crossroads was published on 5 October this year. It has already appeared in Catalan, Dutch, German, Italian, Spanish and Swedish translation. There are three books mentioned here: Javier Marías‘ Tomás Nevinson, Mohamed Mbougar Sarr‘s La Plus Secrète Mémoire des hommes [The Most Secret Memory of Men] and Michel Houellebecq‘s new novel Anéantir [Annihilate]– all of which are certain to be translated into English but, to date, there is no sign of them appearing in translation into English (or, indeed, other languages). I have no doubt that the Crossroads translators received the English text well before 5 October so the translations could appear soon after the English version. Why does this not happen with books being translated into English?

Quite a few interesting book lined up for next year, as usual all from small publishers. I wish you a covid-free 2022 and good reading.